The Journey From Imagination to Execution

I felt good, really good, moments after I shared my first journal entry last week.

That’s rare for me.

I don’t normally have the feeling that I did something cool until maybe a week or two after I release something — when I have a good bit of distance from the process of creating and I’m able to examine the journey from imagination to execution. When I’m able to look at the finished product and ask: Is that what I wanted to make?

I’ve you’ve ever heard me say, “Thank you for making my x dreams come true…"

Like my

Calypso Cowboys Dream

Or my

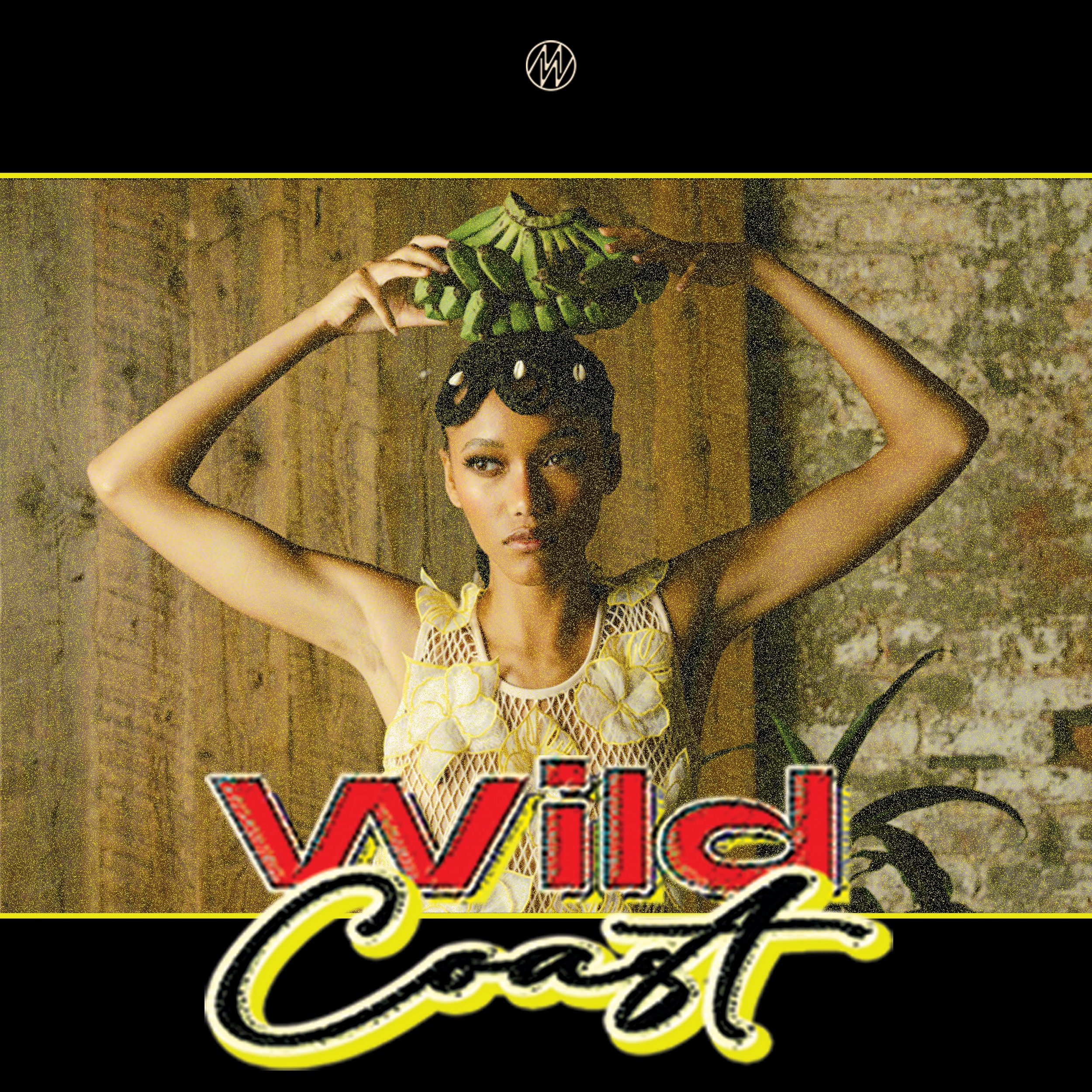

West Indian Goddess

Dream

Or my

Surrealist Barbie

Dream

Or my

Katherine Dunham / Pat Cleveland

Dream

Just know that I really mean that.

Because going from a concept in my head to a tangible, physical execution (a collection, a lookbook, a runway show) are all acts of my dreams coming true.

The challenge is in the journey — the distance between forming ideas in our head, to executing them on paper.

There’s always doubt, anxiety, fear throughout that journey.

If you’ve ever had an idea and gone through that process of turning it into something real, something that you sent out into the world for public consumption and judgment, you know what I mean.

It’s not easy to fight your way through that.

But what I’ve learned over the years is to not shy away from those feelings. Instead, try to embrace them and enjoy each step of the process.

Because throughout that journey from imagination to execution there are so many opportunities for consideration, exploration and innovation.

Let me tell you about the journey I went on to create the Berbice Fringe Dress from my Spring/Summer 2024 ‘Wild Coast’ Collection…

I started the ideation for this collection last Spring around one idea: That I wanted to highlight aspects of Caribbean culture and history that are not often shown in pop culture. Most people think of the Caribbean as a vacation spot — bright colors, sandy beaches, warm sun, laid back and festive atmosphere.

But there is so much more to the Caribbean than just that.

Caribbean people are not monolithic.

The Caribbean is made up of many different countries and each one has its own diverse history and rich culture.

During the course of my research for my SS23 Collection, a full year earlier, I had read about the primarily unknown southern Rupununi region of Guyana — a remote desert plain made up of sprawling ranches and inhabited by indigenous cowboys.

I was fascinated.

Both of my parents were born in Guyana, I used to travel there to visit as a child, and I had never heard of this region, or the fact that there were cowboys in Guyana.

Guyana’s Rupununi Cowboys

This didn’t fit into my concept for Spring ’23, but I knew there was something there that I wanted to explore, eventually, when the time was right.

So when I began ideating for Spring ’24, I knew exactly where I wanted to start.

I dove into research of the Rupununi region and the indigenous cowboys that live there. And that took me down a winding path, exploring the history of Guyana.

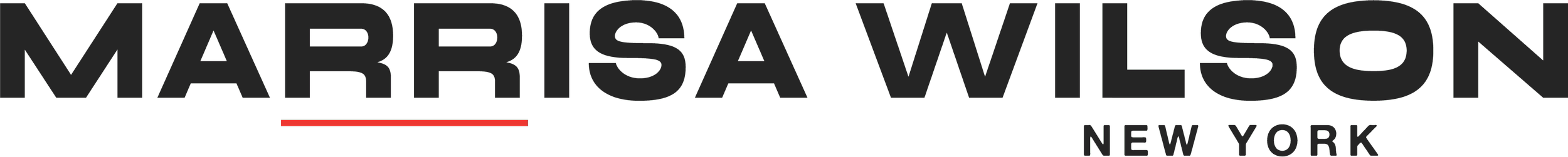

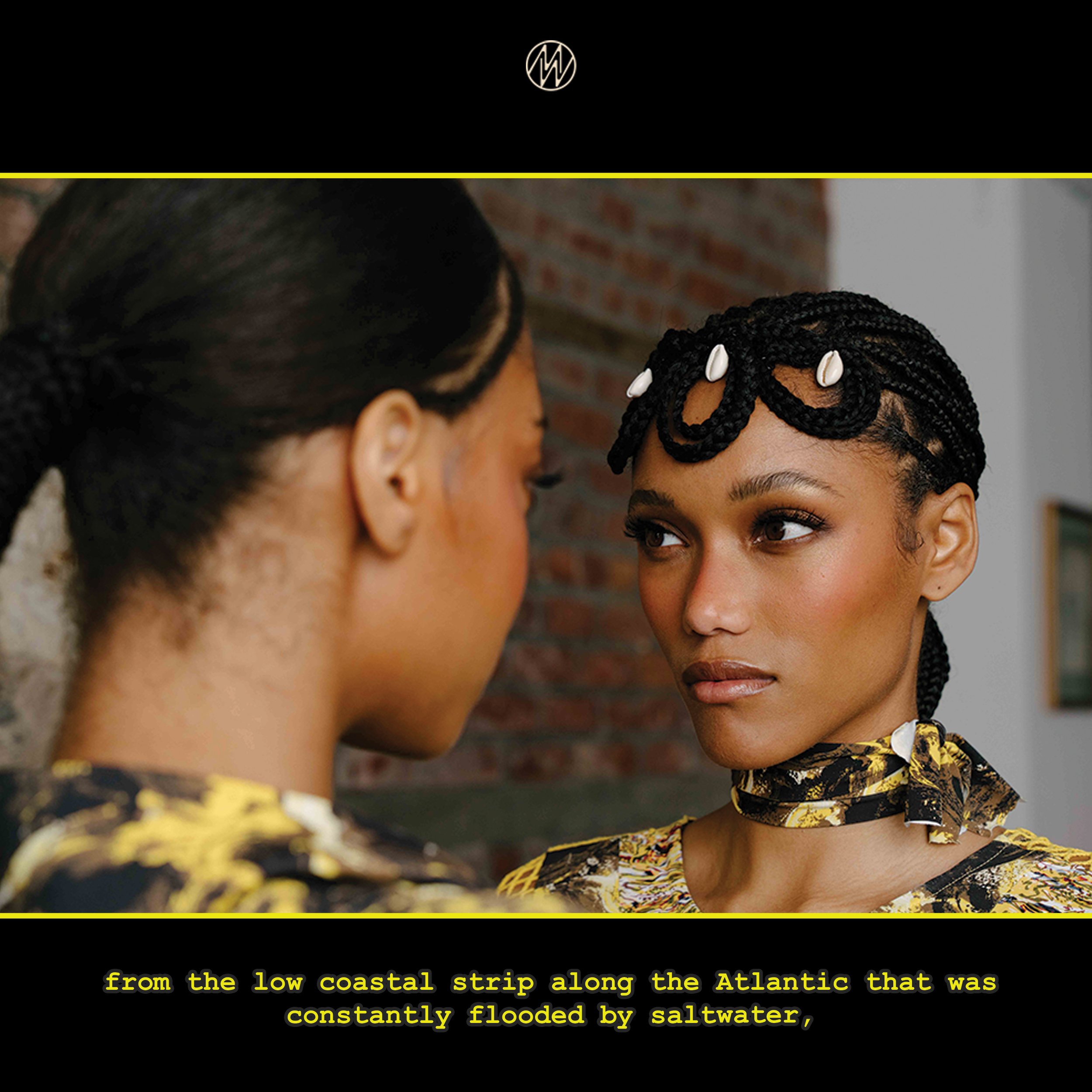

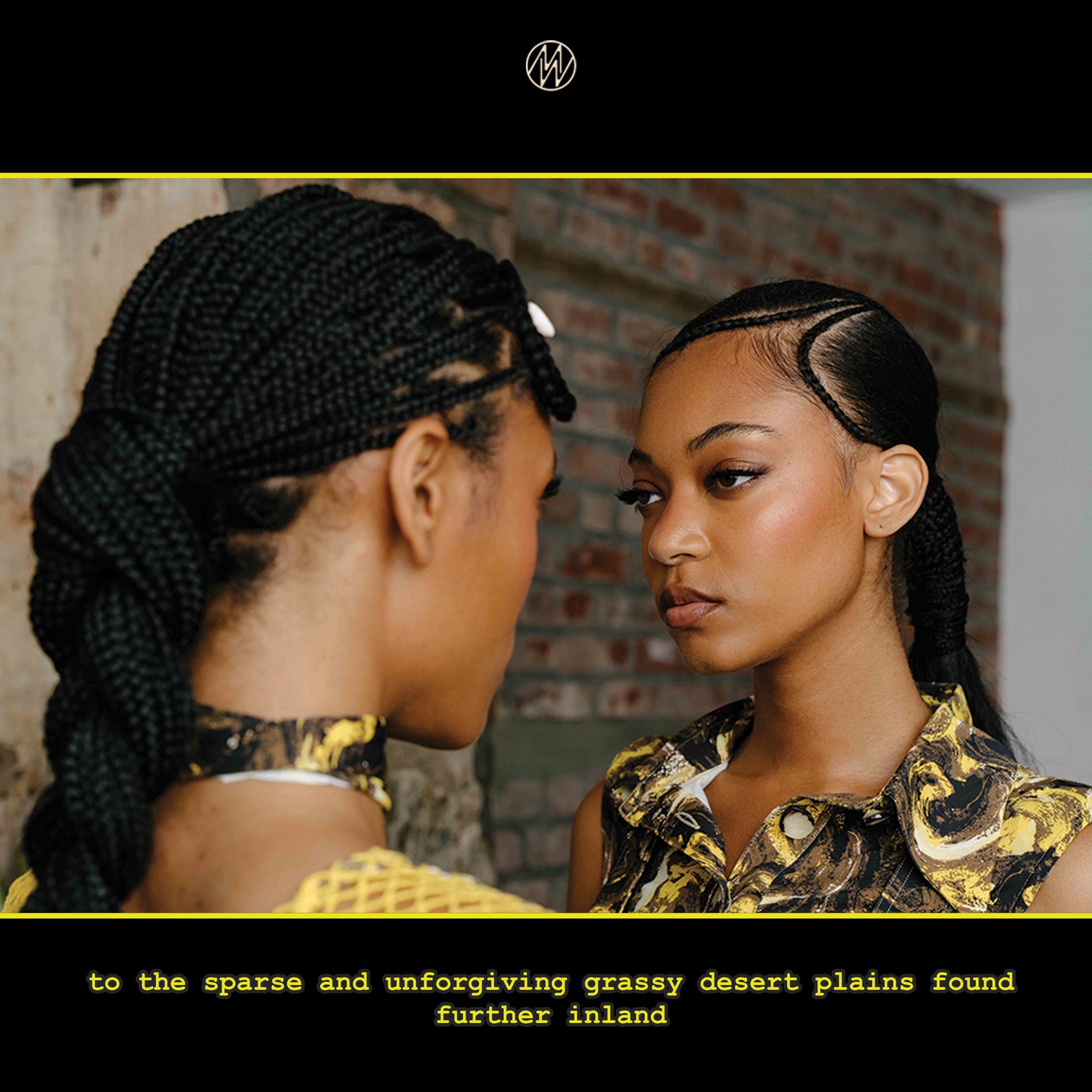

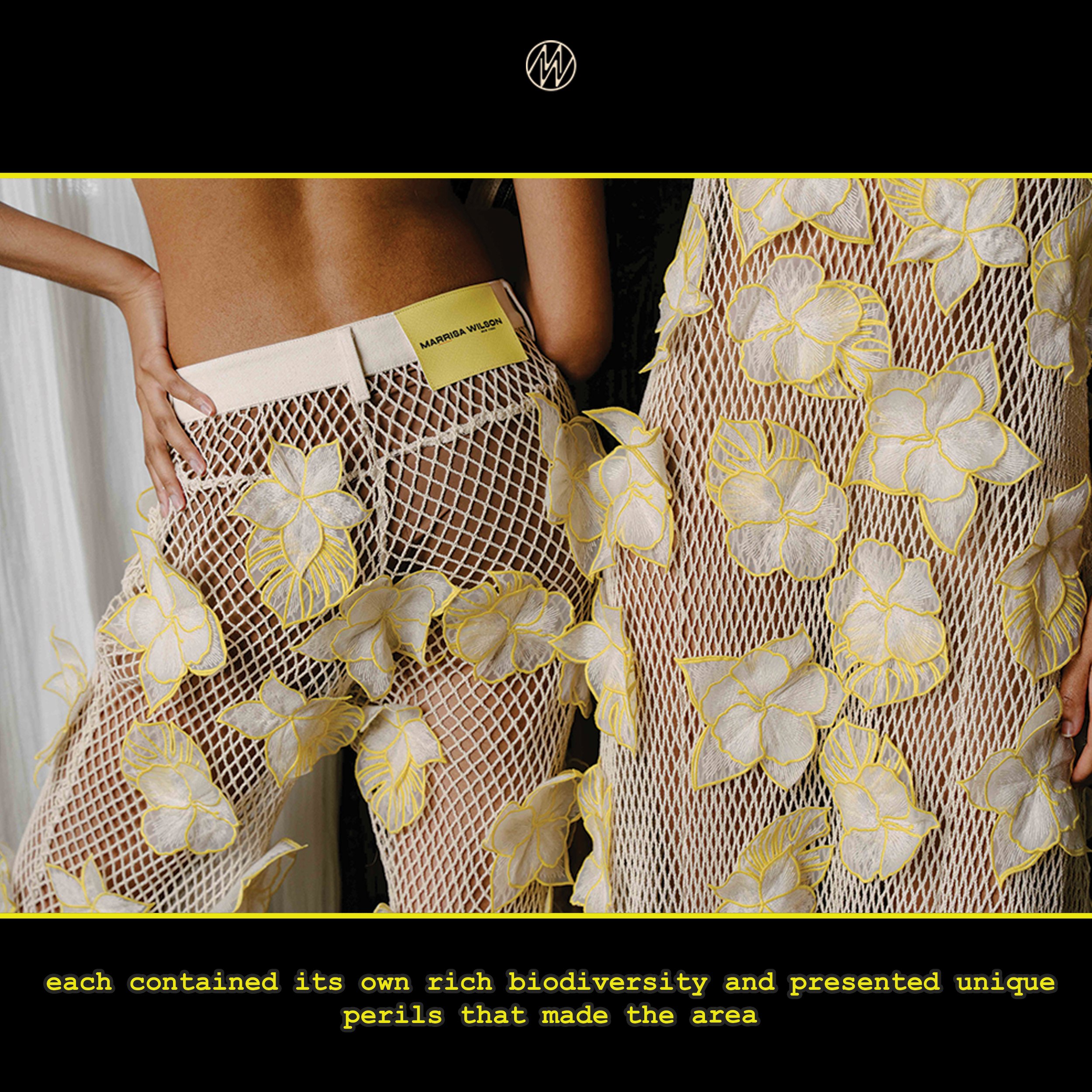

I learned that when European explorers discovered the jungles, swamps and savannas on the Northeast Coast of South America in the 15th century, they deemed the land uninhabitable. The area was a geographic and geologic anomaly. Separated into five natural regions — from the low coastal strip along the Atlantic that was constantly flooded by saltwater, to the sparse and unforgiving grassy desert plains found further inland — each contained its own rich biodiversity and presented unique perils that made the area inhospitable.

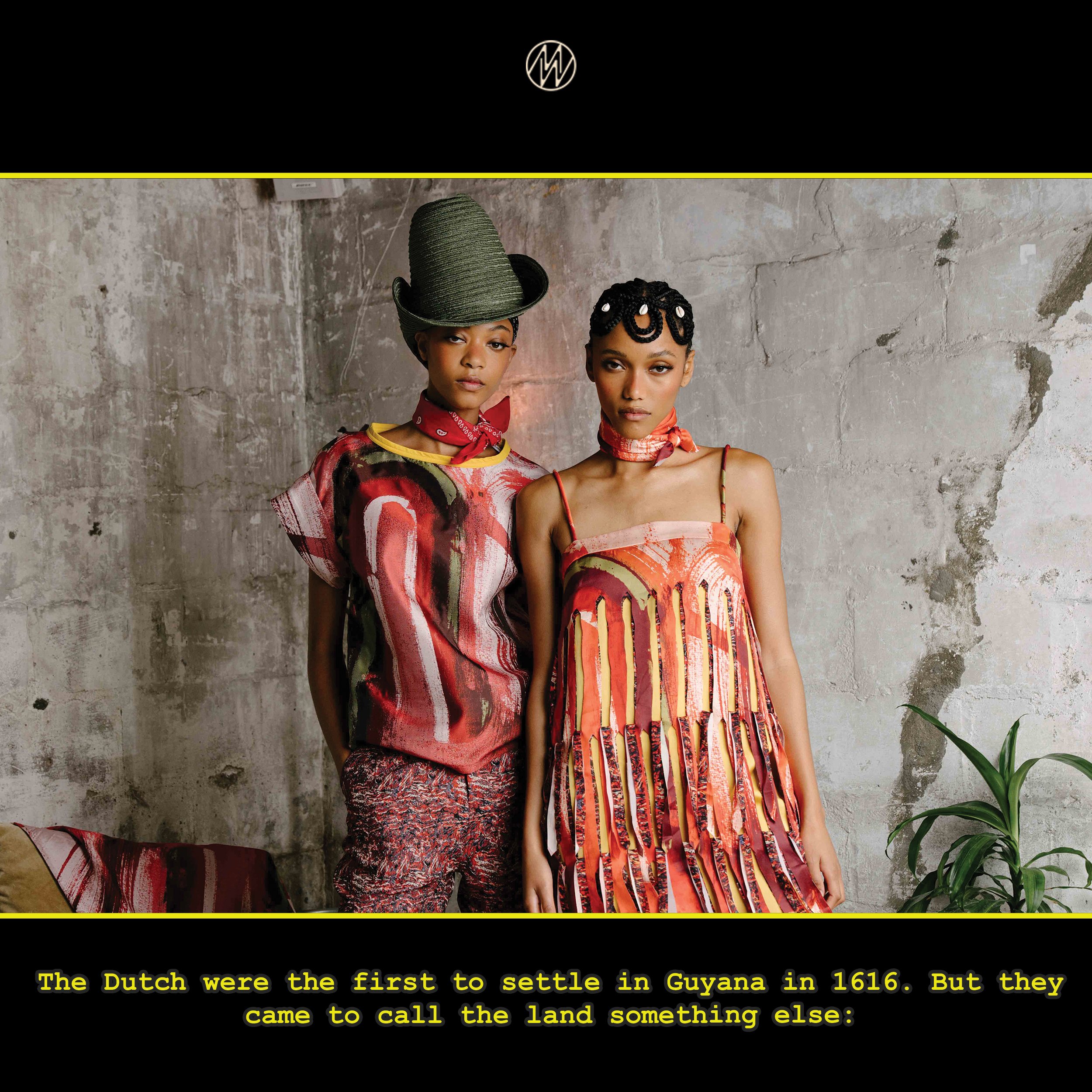

The Dutch were the first to settle in Guyana in 1616.

But they came to call the land something else:

The Wild Coast.

Of course, the country was not uninhabitable. Indigenous peoples had been living there for thousands of years before the European settlers arrived.

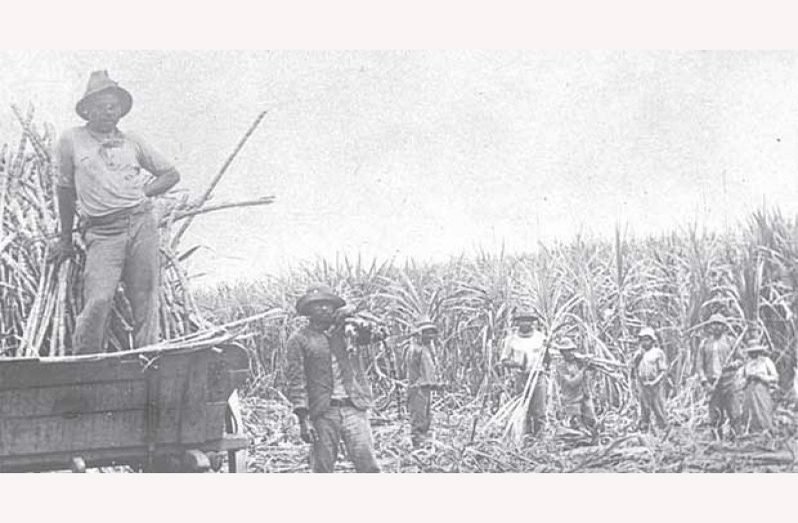

And over the next two centuries — as control of the country changed hands repeatedly from the Dutch, to the British, to the French, and back again, and 100,000 African slaves and Indian indentured servants were brought to work the sugar plantations along the coast— the country became bifurcated.

A sugar plantation in Guyana

The indigenous people, forced to retreat into the vast savanna hinterlands, adapted to the terrain by becoming adept cattle ranchers; while the Africans, freed after slavery was abolished in the 19th century, stayed along the more populous coast and became expert fishermen.

As I learned all of this, my original idea for the collection started to get clearer, and evolve.

Because these days, while most people from Guyana have a diverse genealogy — a unique mix of indigenous, African and Indian ancestry — the people and the cultures have remained starkly divided.

And I realized that I wanted to explore a world where they were not.

I wanted to envision a harmonic blend of these disparate Caribbean cultures.

find beauty through unexpected balance.

And create one singular, soulful Calypso sound.

Now it was time to go from imagination to execution…

When I begin the actual design process, my prints are always the starting point for each collection. I hand-draw and hand-paint each print — to me, they are the first touchpoint of the collection.

It has to start with the art.

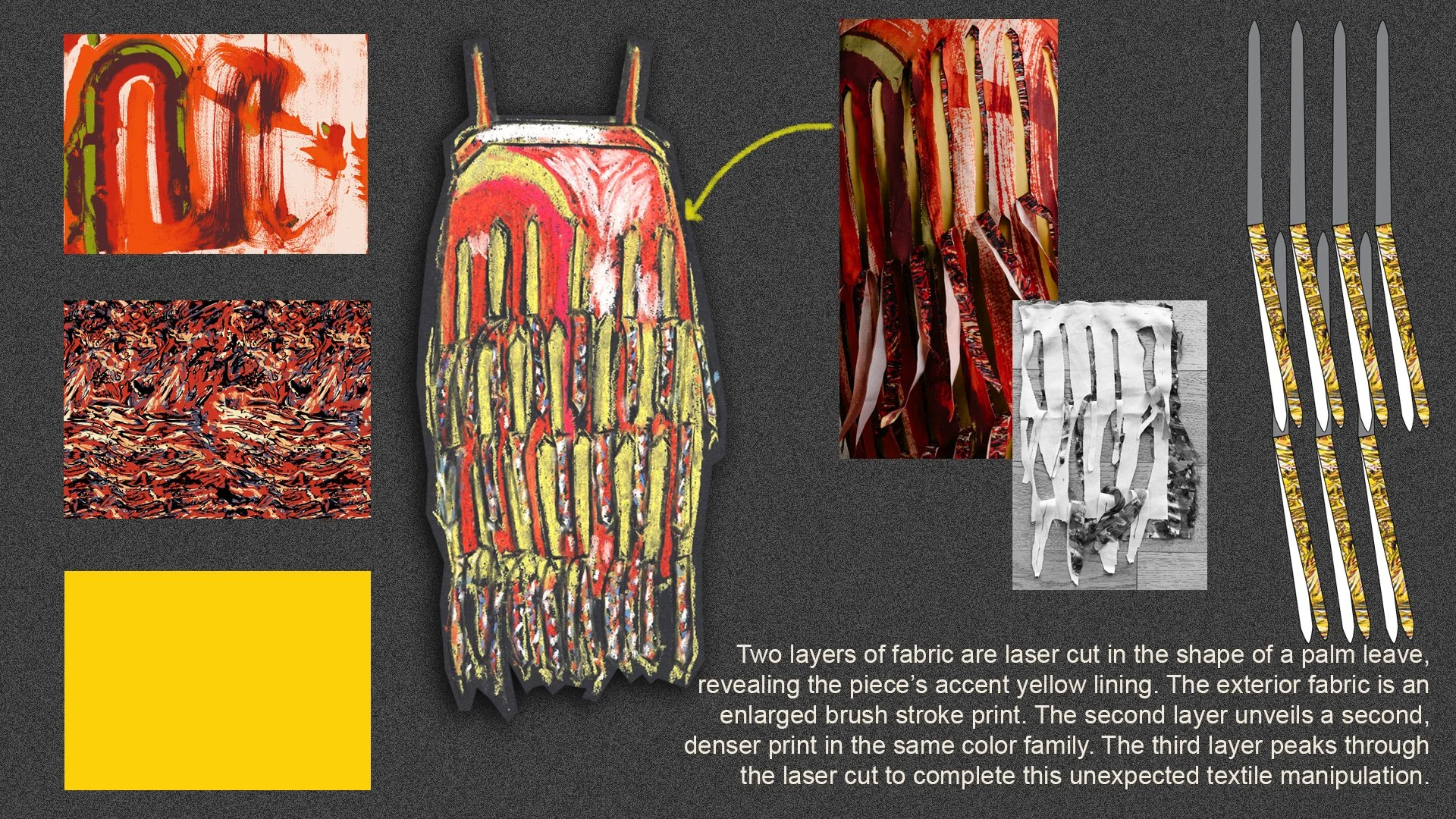

For this dress, I decided I wanted to blend two different prints together to create a visual contrast. First, I created my Grit and Grain print using a dry brush technique, dipping a large, flat brush into a few different colors. This particular brush really absorbed the water, so the effect had significantly less water and was primarily pigment. The dryness of the brush stroke harkened back to the dry, rugged landscape of the southern region of Guyana.

I printed this artwork on a lustrous surface and featured it on the external body of the dress fabric.

Grit & Grain Artwork File

Where the Grit and Grain print is a large-scale gestural print, my Vast Terrain print is balanced in a micro-scale print, intricate and dense. Inspired by the natural layout of sand and rocks, I used fine tip markers to illustrate each sand indentation.

I used the Vast Terrain print as the second layer of fabric in the dress, printed onto our vintage sheer fabric.

Vast Terrain Artwork File

The two layers of the two printed fabrics were then laser-cut and set into the body of the fabric revealing the piece’s accent yellow lining. I developed this technique by researching fringe in traditional Western wear, and then exploring unique ways to execute the concept.

I decided to laser-cut the fringe in the shape of palm leaves, replicating the blades of coconut trees that canopy the country.

It was meant to add movement to the dress and echo the lively spirit of Caribbean culture.

On the back, I added a large pocket with a mitered flap — a very unexpected design detail in a spaghetti strap dress. But throughout the collection I chose to include details traditional in western wear, such as utility pockets and the shape of cowboy holsters.

I wanted these dressier pieces to not feel so overly precious and to blend different cultural aesthetics in unexpected ways.

I chose to name each piece in this collection after a region in Guyana, using it as another opportunity to story tell, deepening the world of the Wild Coast.

The Berbice River, located in eastern Guyana, is one of the country's major rivers. It rises in the highlands of the remote southern Rupununi region and flows northward for 370 miles to the more populous northern coastal plain. These two regions are geographically, culturally and aesthetically distinct from one another, pretty much completely separated.

But I felt that the river acts as their one physical connection. This natural stream of flowing water bonds the vast grasslands and indigenous cowboys in the south with the lush tropics and fishermen in the north.

And so the Berbice Fringe Dress was born.

As you can see, each detail in the dress referenced something specific about Guyana and Caribbean culture — a different aspect of its culture, geography, and people. Individually, they would seem incongruous, incompatible. But when you take them all together, there is harmony and unexpected beauty in the finished product.

That is the journey from imagination to execution.

A journey that took about six months for me to complete, and probably another month after it was finished to have enough distance to appreciate.

Which brings me back to where I initially started this journal entry — that I felt good about putting something out into the world that wasn’t what I traditionally would value as an accomplishment. With my first entry last week, I was able to tighten the distance from imagination to execution to appreciation.

As a creative, that’s a very satisfying feeling.

Publishing that first entry was hard for me to do, because I didn’t know what this thing looked like, or what I wanted it to look like. But I just knew that I had to do it. And that’s scary for me, someone who usually knows exactly what they want to create, exactly what they want to say, and exactly how to make it happen.

It’s difficult to feel like you need a new challenge and yet not really know exactly what it is. I think when you go in one direction for so long, you spend all this time learning, studying, working, gaining experience — and not enough time appreciating that journey.

I pride myself on my in-depth research methodology. And if I look back now at all of the work I did to create this one dress — while I am absolutely in love with how the final imagery came out — the research, the process of coming up with and fusing together all of these different design elements into one coherent vision, is what I am most proud of.

It is the journey that truly fulfills me.

So do me a favor.

Recognize every time you took an idea in your head and, against all odds, turned it into reality. And give yourself some credit. Because, these days, the odds feel more and more like they are being stacked against us. 💛

Marrisa Wilson is the Creative Director and Founder of MARRISA WILSON New York. The first generation Guyanese-American designer uses her collections as a medium to explore culture and history through the lens of her Caribbean heritage, with artisan hand-painted prints, high-quality custom fabrics, expert surface treatments and unique textile manipulations.